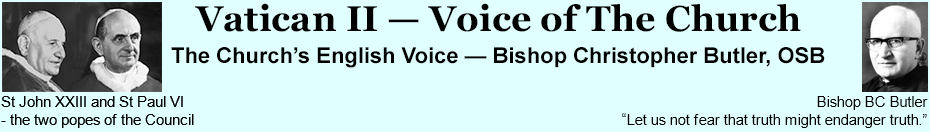

Bishop B.C. Butler OSB - Apostle of Vatican II

by Arthur Wells

"The Roman Catholic people in England have, so far, only a very shadowy and imperfect idea of what it all means - they are preoccupied with little changes in Mass ceremonies etc. To me the Council is potentially one of the biggest things that has happened in the Church since 1054.

So wrote Basil Butler from Rome to his sister Mary on 26 October 1965. He went on:

But so many people, even if they have been members of the Council don't seem to see it. It is rather like the question of appreciating the real significance of the New Testament: some people see nothing but a host of critical questions, while for others it is the splendour of a tremendous revelation.

That letter was written towards the close of the final session of Vatican II which had opened in 1962 and which the then Abbot Butler had approached with some trepidation. Recalling it later he wrote: "I looked forward to the Council with more foreboding than hope ..... A meeting of some 2000 prelates averaging in age about sixty years was unlikely to be a progressive tribunal ..... I feared another dose of authoritarian obscurantism."

The purpose of this general article on Butler and the Council is to recall the importance of both at a time when each is being lost from sight, perhaps through a recrudescence of the very authoritarianism, which Butler feared and about which senior voices are currently raised: [Quinn, Arns, König, Austrian bishops & NZ bishops]. Butler was, of course, clearly in favour of 'authority', one of the many grounds for his conversion. At the same time, he was deeply concerned about how authority was exercised and was utterly opposed to the obscurantism, which was an unhappy feature of ultramontane Roman Catholicism. Freedom for Scriptural research was the subject of one of his many telling speeches at the Council (6 October 1964). Despite the problems of producing a clear theme in a brief introductory piece, when so many themes might be tackled, it is hoped that Butlers effort to influence the Church towards openness and to unity - through the Council - will be clear. In this and in his breadth of vision he was unique among the British. A senior monk of Downside comments on crucial qualities:

[He] was very hopeful about the Church's future, heart and soul in proclaiming the teaching of the Council and in some matters open to daring theological speculation. But he was also very tenacious of the dogmatic quality of Catholic beliefs .......

To return to the Council in 1962, after his initial foreboding, and having studied Pope John's opening speech, Butler had reported to his sister that the Pope's words "breathed hope". Butler was sixty; as the Council developed, his own hope and enthusiasm increased. Fortunately for posterity, brother and sister corresponded regularly. Significantly, Miss Mary Butler was herself a senior teacher and was also theologically qualified. But for that correspondence, there would probably not have been such an important record over many years giving answers from an authority at the centre of affairs to penetrating questions concerning the Church. Those questions and comments to the abbot came from a highly knowledgeable correspondent and we owe a considerable debt to Miss Butler, both for prompting the responses and for the loan of the letters. They clearly acknowledge her competence and throw important light onto many events of the time from one of the finest minds of his generation. That judgement, forecast by his triple first will later be emphasised from diverse sources; but now affectionately from his youngest brother Archdeacon Hilary Butler: "Basil was a walking intelligence".

Basil Butler was born on May 7 1902, the son a of a Reading wine merchant. He went to Reading School and won a scholarship to St John's Oxford. He had five siblings, his sister Mary being born in 1907. But for the scholarship, family finances would not have stretched to Oxford. He studied for the Anglican priesthood, but became a Roman Catholic in 1927, and taught classics at Brighton College and at Downside Abbey. He entered the monastery in 1929 and was ordained priest in 1933. He died in 1986. It seems that Basil and Mary were always close; she had become an admired teacher, second mistress of an important school. She was about to be appointed to a headship, when her father died and as was the caring family custom then, she took a lesser post to be near and look after her mother. Abbot Butler, "Christopher" in religion, but always Basil to his family had no need to spell out to his sister the significance of 1054. She knew well the possibilities opening up during the Vatican II debates, which concluded with many significant constitutions notably on the Church. The letters are full of references to prayers for the success of the Council; from one letter:

I'm so glad you prayed for the Council at church last Sunday. Did I tell you that the Bishop of Bristol, in a pastoral letter, asked his people for prayers for the Council and, in particular, for the Bishop of Clifton and the Abbot of Downside?

Widely known for his gentle, rather formal courtesy Butler added, a mite quaintly to us now: "I thought this was very decent of him" (18 October 1962). How many Roman Catholics know of the Anglican and other churches in which prayers were regularly said for the Council's success?

The Calling of the Council

It was with some experience of authoritarian obscurantism in the communion which Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli found himself leading in 1959, which prompted him to call an ecumenical Council. The new Pope - John XXIII spoke in a homely way of "opening windows" and "blowing off dust", but at the same time:

The greatest concern of the ecumenical Council is that the sacred deposit of Christian doctrine should be guarded and taught more effectively.

Beyond the opening of windows, it was the evident desire of the Pope for Christian Unity, which so captured the affections and hopes of other Christians and led to their prayers. To return yet again to 1054, if the breach with the Orthodox might begin to be healed, and there is no doubt that responsibilities for the breach lay on both sides, then there could be increased hope that the equally tragic divisions of the 16th century might also be mended; there too, faults were not one-sided. This ecumenical thrust of Pope John's vision as perceived by Butler will receive due emphasis in the writer's coming book on him. Re-stated by Pope John Paul II, it remains a source of optimism. It was in this hopeful and developing atmosphere in Rome in which Butler was called to work, to observe and to report. Not only did he write to his sister, he reported assiduously to his community at Downside; this was a prime duty for him.

The Teaching and Reception of the Council

If Butler was right about Vatican II's outstanding importance since the Great Schism, then subsequent developments in the Western Roman communion are disturbing to those of us who believe that he was right. For such a "millennial" event to be so little understood, except by specialists, or even known about in any depth, because the Council has been so little taught, is a matter for deep concern. As to our principal luminary at the Council, Dom Christopher Butler himself, it is rare that he is readily called to mind, again only by specialists. If the name Butler is enquired about, it is possible that Dom Cuthbert, also Abbot of Downside, but 40 years earlier surfaces, or even Alban Butler, the 18th century author of the Lives of the Saints... 'Alban' was the best that a Venerabile seminarian, whom I met in Rome could manage. Whether among ordinary priests, or ordinary people, there is a lack of historical perspective.

Accounts of the Council

Given the widespread ignorance, familiarity with important documentation cannot be taken as read. Vatican II, like all formal deliberations was documented by the standard processes in the Acta Apostolicae Sedes (AAS), ie the Vatican Gazette - a sort of Hansard. Often more immediately available were significant, if informal, "free-lance" reports. A surprisingly accurate account was by a racy American whose identity was never certainly established; his nom de guerre was Xavier Rynne. Absolutely central, are the Council documents themselves, translated into English first with commendable speed (1966) by the Jesuit, Walter Abbott and later (1975) by the Dominican, Austin Flannery. These are the readily available English versions. Written for a different purpose, Storia del Concilio Vaticano II does not just deal with the documents, but emphasises that the Council was not solely an event between 1962 and 1965 resulting in a set of decrees, but a complicated process. The Storia team is directed from Bologna University and led by Prof. Giuseppe Alberigo. Four volumes of this master-work were completed by the end of the last century and the fifth and final is due in 2001. The English translations are being directed by the principal co-editor of the whole work and director of the team in the USA, the Revd. Prof. Joseph Komonchak of Washington DC. This great work has taken more than 35 years to complete and it confirms Abbot Butler's significance.

Butler's Importance at the Council

Three random opinions from very differing view-points will suffice to illustrate Butler's importance at the Council. Writing in "The Tablet" (Dec. 1964), Christopher Hollis MP said:

Of the English ecclesiastics the man with incomparably the highest reputation in America is Abbot Butler. I do not remember a single American Bishop who did not mention his name first among English ecclesiastics.

After Butler became a Bishop and something of a national favourite on Radio and TV; (another chapter entirely), Graham Greene's friend Fr. Leopoldo Duran reports a meeting between Butler and Greene: "....we spoke at length about Bishop Christopher Butler, the distinguished theologian, scholar and writer. We both agreed that he was one of the best intellectual minds in the Catholic church and that his thinking left its mark on the Second Vatican Council." They compared Butler's career to Newman's and wondered: "It may be that he was not made a Cardinal because of his age. Or did he refuse it himself because he did not want to look after a London diocese? As it happened, they elected (sic) another Benedictine Basil Hume to be cardinal." Fr. Duran might have been expected to know the procedures better, but the comments demonstrate the humility and closeness with which Butler had kept his counsel, as will appear. Another weightier opinion comes from Prof. Adrian Hastings: "In all this, he [Cardinal Heenan] was immensely different from that other leading English figure at the Council, Christopher Butler, Abbot of Downside. He was one of only a handful of genuine theologians to be a full voting member, not just a "peritus". [Hastings refers to ALL 2000 prelates]. He saw the problems as Heenan did not." Then:

He would now increasingly come forward as the one senior English voice, at once unimpeachably loyal to Rome, yet cognizant of the full weight of contemporary theological scholarship and able to shake himself free of the simplicities of ultramontanism.

That view is all the more persuasive if the writings and subsequent activities of other bishops who attended the Council are studied. Despite good intentions, Cardinal Heenan's and Archbishop Worlock's books displayed no depth of insight into the range of issues at stake.

Partly because of this lack of real understanding and steady, purposeful teaching from the bulk of the hierarchy, and certainly for other reasons also, the post-Vatican II Catholic Church, for all practical purposes has retained the post-Vatican I model of the pyramid. Even the centralisation which was criticised by many bishops attending Vatican I in 1870 has increased yet further. The Council theology of the Church introduced a concept of 'œCommunion'œ, but in practice the pyramid remains as before. Clifford Longley describes well the "Counter-Reformation", pyramidal model in The Worlock Archive. But that book is mentioned mainly because of its historical value and because it throws embarrassing light on the relative incomprehension, pettiness and disarray of the English & Welsh hierarchy. After one hierarchy meeting Butler is reported to have said: 'I could have thrown the furniture!' When it came to the hierarchy discussions at their temporary HQ in the English College about who to nominate for the various commissions, to his great credit, the then Archbishop Heenan threw the cat among the pigeons by saying that the only man suitable for the theological commission was Abbot Butler as there were no theologians in the English and Welsh hierarchy!. That should prompt many questions, but one question may be: "Why was the Abbot of Downside at the Council?"

Abbot Butler Emerges

Butler was tailor-made for the task of contributing to the Council - almost providentially it seems. For present purposes, there is little need to enlarge much on Hastings' comment about his strengths. A distinguished New Testament scholar, with a strong interest in philosophy, he had been a teacher and then Headmaster at Downside school. He was first elected Abbot of Downside in 1946 and subsequently twice more in 1954 and 1962. His distinction in the scholarly Benedictine world was such that in 1961, he had been elected as Abbot-President of the English Benedictine Congregation. That made him a major religious superior and it was in this capacity that he was called as a full member to the Council. The surprise which Pope John XXIII sprang on the world is legendary and Butler's own apprehension has been mentioned.

It was providential also that he came from a devout, close-knit Anglo-Catholic family, which did not follow him into the Roman Catholic church. Happily Butler was one of those blessed converts who was grateful for the deep Christian roots in which he had been nurtured. This background gave him a head start in understanding other denominations, compared with many Council Fathers, who both started and finished the Council knowing little of the strength of the Orthodox case, of Catholic weaknesses at the Reformation, or fully grasping the Ecumenical imperative. This, although only loosely indicated by Pope John had nevertheless been one of his reasons for calling the Council. The imperative to Christian Unity has more recently been signalled by Pope John Paul II. As well as being a polymath peritus in his own right, therefore, Butler also had a grasp of ecumenical needs not shared by many Council fathers.

It is small wonder that he made a mark very early on. Rather reserved, he writes privately of his nervousness about making his early speeches in the Aula - the Council chamber. As a classicist he spoke Latin, and this ability was doubly important because he also understood other speeches, where many Anglophones did not. He was listened to attentively, particularly by the Anglophones, because they could both follow him and what he said was invariably to the point.

To his own surprise, Butler found himself not having to plough a lonely furrow, but abreast of a large swathe of theological opinion from Europe. However, much of the Catholic world, including bishops, priests and laity was largely ill-prepared, and for many the Council began at least, as a puzzling and disturbing event. But equally, there were pockets where people who also cared as deeply about the Church, felt that things were not right and saw Pope John's vision as vastly important, not just for the Roman Church, but for Christianity as whole and therefore for the world.

High among Butler's interests were Newman and Von Hügel. The latter had enunciated that true religion requires: Intellect, Institution and a Mystical element - that is a solid prayer life for both individual and institution. Butler was an exemplar in all three elements, most certainly in his prayer life. An Old Gregorian who was a boy at the school when Butler was Headmaster said: "Bit of a saint really". A Westminster priest who knew Butler well and worked closely with him said simply: "I revered him'.

Not many know of the conclusive evidence that Butler was a prime candidate for the Archbishopric of Westminster in 1963, after Cardinal Godfrey's death, although more are aware that he was in line after Heenan. There is a wry note in a letter to his sister of his hope that they wouldn't get him second time round!

In Conclusion

The thesis advanced is that Basil Christopher Butler was one of the most exceptional English Christians in the last century and that he had more influence at the Council than any other Anglophone. There are multiple aspects of Vatican II where he made an outstanding contribution and which would justify further consideration before his centenary in 2002. This article began with a quotation from his letter of October 1965. It continued:

The question remains, of course, how soon and how thoroughly it [Council teaching] will be put into operation. That is one of my major concerns now: how far the Council's work is going to be made fruitful in the post-conciliar Church.

Almost forty years later, Pope John Paul insisted that we must carry Vatican II with us into the new Millennium. Christopher Butler would be a good guide; acknowledging how educative it had been for him, he stressed:

The Church is in Christ as it were a sacrament or sign and instrument of inward union with God and of the unity of the whole human race.[my italics].

He concluded for himself:

The Council has helped me to see that this notion of the sacramentality of the Church is basic to our understanding of her.