The Dogmatic Constitution 'On The Church'

(De Ecclesia Proclaimed by Pope Paul VI November 21, 1964)

Introduction to Butler's Text

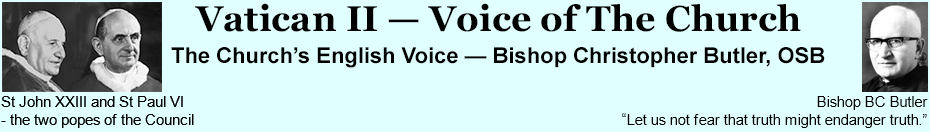

The following text by the then Abbot BC Butler OSB was the Foreword to a book published just one month after the promulgation of the document De Ecclesia ('The Constitution on the Church', DLT London. 21 Dec.1964.)

Background to the Council Times

The Council, which had been two years in preparation, and which lasted four years, ended over forty years ago. The preparation had been in the hands of the Roman Curia and was judged somewhat unsatisfactory when the world's bishops assembled. It is not now easy to appreciate the ferment of popular interest and activity at that time. People who recall it vividly are becoming rarer. Those who do recall the event, remember that as the Constitutions, or Decrees, were promulgated, these important official texts were publicised almost immediately. Also many commentaries followed shortly after. The commentary writers in many cases had themselves been active participants in the Council either as members, or as experts (periti). Abbot Butler was both a member and an expert. As a classical scholar he was an accomplished Latinist, so that he knew exactly what was going on, when many members, i.e. Council fathers did not. Consequently, in the English-speaking world he was one of the most sought-after commentators. The sense of freshness, renewal and enthusiasm is evident in these various contemporary writings and the foreword by Christopher Butler which follows is a prime example.

Many of those contemporary books and articles are long out of print, but the potential of the internet gives us much broader access than in the sixties to those vibrant first-hand accounts of the Council, which were produced while the experience remained fresh in the minds of the participants.

This new potential is timely in view of the passing of the years, of the lack of knowledge of the period, of the various subsequent uncertainties and the consequent lack of clarity about Vatican II.

Background to the Book on De Ecclesia

The volume from which the Butler Foreword is taken was valuably and rapidly produced at a time of great expectation of renewal. It was produced specifically to disseminate the single document 'On the Church'. It is notable that it was published (Dec 1964) while the Council was still in progress - and more importantly - that the foreword was written by such a significant Council Father as Abbot Christopher Butler OSB. He was also one of only four elected - as distinct from centrally appointed - members of the Theological Commission. This commission in which Butler played a significant part, had the key responsibility for overseeing doctrinal matters. Its chairman was the redoubtable and deeply conservative Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, prefect of the Holy Office, successor to the Inquisition, now renamed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF).

Butler helped shape the document on The Church and his account is therefore distinguished by its authority. More detailed commentaries on aspects of De Ecclesia from the same book by other hands and also from other books appear, or will appear elsewhere in this section of the website.

The Dogmatic Constitution - De Ecclesia

The document itself can, of course, be accessed via this website. A study of the text is strongly recommended as a sine qua non for any serious student. It is worth reiterating that generally speaking, the teaching of an ecumenical Council is that of the highest magisterium of the Church. Widely considered to be the principal achievement of the Second Vatican Council De Ecclesia is also known by its opening words - Lumen Gentium. Many other Council documents effectively depend on this Constitution '˜On The Church' and it is strongly linked with the only other Constitution given the status of '˜dogmatic', that 'On Revelation'. Responsible as a distinguished scripture scholar, for many contributions on Revelation also, Butler was not alone in considering that latter Constitution, known as: Dei Verbum as of equal importance with De Ecclesia. Both produced significant changes in ecclesiology, but at all times during the Council deliberations, the Council Fathers remained faithful to Pope John's words when opening the Council:

'....the church should never depart from the sacred treasure of truth inherited from the Fathers. But at the same time she must ever look to the present... to the new conditions in the modern world, .....'

Abbot Butler's summary of the Constitution follows; the sub-headings have been added for the reader's benefit to identify and highlight important themes that are expounded in the text.

Arthur Wells

Foreword to De Ecclesia

by Dom Christopher Butler OSB, Abbot of Downside

The programme of "aggiornamento", set before Vatican Council II by Pope John XXIII, was capable of two interpretations, and a history of the Council could be written around them. There were those (and they included some in positions of high authority and great influence) who would have been content with a protest, suitably fortified by anathema, against the grave and insidious errors of our time, along with some additions to, and subtractions from, the Corpus of Canon Law. The Synod of Rome, held shortly before the Council, would have been the type of what these would have desired. Others saw the challenge to the Church in a very different light. The number of these grew as the Council debates went on.

Most of us had grown up in an almost exclusively Latin Catholic environment, and under the sway of a theology and practice which, while reinforced by the outcome of Vatican Council I, had their roots far back in the Counter-Reformation, in medieval struggles between Church and Empire, in Byzantinism and in the so-called Peace of Constantine.

The Church reflects on herself

The Council brought us new insights. We found ourselves face to face, in liturgy and debate, with the oriental Catholicism of the Uniate Churches, so remote from the scholastic theology and sober Latin worship of the Western Church. We could no longer shut our eyes to the needs and aspirations of the Church in the Afro-Asian countries, where any policy, based on Hilaire Belloc's dictum, "The Faith is Europe and Europe is the Faith", would be doomed to disaster. And, perhaps above all, we were confronted with the representatives of a great theological rebirth which goes back to the pre-war years but has grown in scope, depth and purpose in the countries of Northern Europe (excluding the British Isles) largely as a result of the devastations of the war itself.

We began to see that the Church is something far greater than the Western Patriarchate. We began to realize that, if she is to measure up to her own inexhaustible potentialities and to the demands of an age without precedent in human history, her leaders must learn to think radically and to act with audacity. Especially was it necessary to engage in basic theological thinking. In particular, the Church must reflect upon herself, her nature and limits, her functions and her mission. Such was the business emphasized by the new Pope when he inaugurated the second session of the Council. A Constitution on the Church had been drafted before the Council opened, and had been debated and strongly criticized during the first session. Before the second session, it was superseded by a new draft, of which the Constitution passed and promulgated on November 21, 1964, is the outcome.

The Constitution is a stepping stone

I have no hesitation in saying that the Constitution is a great document, even though, being the fruit of the Holy Spirit's working in imperfect human beings, it is a stepping-stone and not a final accomplishment. Everyone will see it according to his own lights and predispositions; for each of us it has a message. I shall try here to indicate some features of it which seem to me to be important.

First, then, it is a negative virtue of this Constitution, as of all the documents that have so far emanated from the Council, that it gives us no new definition of faith, no fresh anathemas. The nearest it comes to forging a new definition is when, at the key point of its exposition of the nature of the episcopate, it uses the phrase: "this sacred Council teaches, etc." This is something less than: "the sacred Council solemnly teaches", and is on an entirely different plane from: "the sacred Council defines".

It is sometimes necessary, or useful, to define an article of faith. But it must be observed that every fresh definition sets up a further obstacle for those who are approaching us from outside. In particular, when the Christian world is becoming more and more aware of the need for "reunion", it is well to bear in mind that the post-Tridentine definitions of the papal primacy and infallibility, and of the Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Our Lady, have given an edge to the doctrines they enshrine which makes Catholic ecumenism more difficult than it would otherwise have been.

A Pilgrimage and Spiritual Fellowship

Secondly, the Constitution sees the Church, in her earthly pilgrimage, first and foremost as the spiritual fellowship of her baptized members, and only secondarily, and as it were consequentially, as a hierarchized communion. The great chapter III on "the Hierarchical Structure of the Church" is preceded by one on the People of God, and is immediately followed by the one on the laity. The pope and the other bishops, with the priests and deacons, are presented to us as established for the service of God's People, and the Constitution is almost entirely free from that note of "triumphalism" which has sometimes disfigured the image of the Church and which was so scathingly attacked by Bishop De Smedt of Bruges in the first session of the Council. Not only are the clergy the servants of the People of God, but the Constitution points out the role in the Church's life of the "charismatic" gifts of the Holy Spirit which are bestowed indifferently on clergy and laity alike, and which provide the dynamic, transforming element in the Church's history.

The Wider Christian Community

Thirdly, the Constitution's treatment of the questions raised by the existence of non-Catholic Christians and their communions is fully positive and respectful. It is true that, in the crucial paragraph in chapter II which explicitly adverts to non-Catholics, the language is vague and curiously un-theological. But it remains always friendly, and may be said to pave the way for much more definite and forward-looking statements on this subject in the Decree on Ecumenism, which was passed and promulgated along with our Constitution.

The Universal Call to Holiness

Fourthly, as a monk I am glad that the Constitution treats of "the Religious" (chapter VI) outside the context of the Church's institutions. Obviously, religious orders, congregations, and monasteries are institutions in the Church, but they are not, like the apostolic ministry, of direct divine foundation. It is more to the point - and the Constitution makes it easy - to see the religious vocation as a call to a special mode of realization of the universal Christian vocation to holiness which is the subject of chapter V.

The Blessed Virgin Mary

As a result of the narrowest majority in the story of the Council up to date (apart from some elections of commissioners), our Lady is treated in a chapter of this Constitution, not - as had been originally intended - in a separate document. It must be conceded that this decision, and the contents of the resulting chapter, caused a great deal of heart-burning. I can only say that I personally believe that devotion to our Lady will gain in quality through the Council's resolution to "contain" Marian doctrine within the framework of the theology of her divine Son and of the Church of which she is both type and "pre-eminent member".

Ecumenical Councils: the Pope, the Bishops and Collegiality

The Constitution will certainly be remembered for its treatment of the episcopate in chapter III, which comes as an overdue complement to the doctrine of Vatican Council I on the papacy. Centuries of discussion were brought to a close when, in 1870, it was determined that the pope has a universal, ordinary, and immediate jurisdiction over the whole Church and all her members, including the other bishops, and that his definitions of faith are irreformable "ex sese et non ex consensu Ecclesiae" (of themselves and not as a result of the [subsequent] consent of the Church).

Nearly a hundred years have elapsed since Vatican Council I broke up, never to be reassembled. During that period a tendency developed, especially in theological circles geographically close to the Holy See, to see the papal primacy as the unique fountainhead of all magisterial and governmental authority in the Church. This tendency is neatly expressed in the theory that even the supreme authority of an Ecumenical Council is something which is given by the pope. The logical conclusion of this tendency would be to regard bishops as mere delegates of the successor of St. Peter.

It is not surprising that there was a strong reaction on the part of the so-called conservative wing of the Council against the proposal to affirm the intrinsic "collegial" authority of the Catholic episcopate as a whole. It was urged that, if it were stated that the "college" of bishops has universal and supreme authority over the whole Church, this would involve a limitation upon the powers of the pope and so a virtual contradiction of the decisions of 1870. Thus the stage was set for a theological drama, played out in the general meetings of the Council, in its Doctrinal Commission, and indeed behind the scenes, of which our third chapter is the result.

Although it was the doctrine of collegiality that stole the headlines, the crux of the Constitution's teaching on the episcopate is perhaps contained in the affirmation that a bishop receives in his consecration the "fullness" of the ministerial priesthood derived from Christ, and therefore, as is explicitly asserted, not only the "office" (munus) of "sanctifying" (by sacramental ministrations) but the offices of teaching and ruling. Thus episcopal authority is not something received from the pope, but something given directly by God in the sacrament of holy orders.

In the end, the whole Constitution was passed with only half a dozen negative votes - a remarkable contrast with the final voting in 1870 on papal infallibility, when, it is true, there were only two dissenting votes (out of a much smaller number of members), but over a hundred conciliar Fathers absented themselves in order not to feel obliged to vote "non placet".

Historically, it is interesting to note that the doctrine of collegiality is the traditional one, and that in fact it was taken by the moderate papalist wing of the first Vatican Council as the basis from which to argue for the unique position of the pope. Unilateral papalism is an exaggeration, and particularly a very modern exaggeration.

It is hardly necessary to point out that this renewed emphasis on the immediate divine authority of the bishop and the supreme authority of the collegial episcopate is important for ecumenical dialogue, especially with our Orthodox and Anglican friends. Such dialogue should also be facilitated by the fact that the theology of the Constitution is profoundly biblical in its inspiration, and comparatively free from the conceptual elaborations of modern scholasticism. This will be still better appreciated when the Constitution on Revelation has been promulgated. Taken together, these two Constitutions form a monument to the revival of biblical scholarship and theology in the Church.

The Importance for the Future

Finally, it must be remarked that the value of the Constitution on the Church is largely potential. It is a document not immediately directed to practical changes. But its worth for the Church and for the future of Christianity will depend largely on our willingness to understand and communicate its message, and to give practical expression to its implications. Its key doctrines are: the common priesthood of all the faithful, originating in their baptism: the intrinsic life of the local Church, centred in the Eucharist and the ministerial priesthood and episcopate; and the collegial authority and responsibilities of the bishops within the hierarchical communion of the Church. Together, these doctrines could be the basis for far-reaching practical changes, and could prepare the way to a Church in which the life of the members was not inhibited but promoted by the "presidency in charity" of the See of Rome; a Church with great elasticity and creative adaptability, such as will be needed in a world where the movement toward human unity is compensated and enriched by a keen realization of the place, within the wholeness of our history, of local variations and initiative.

Abbot of Downside

Somerset, England

Concluding Note

Butler was writing in the immediate aftermath of the promulgation of the document 'On The Church'. Comparing his summary with the work of other Fathers and experts, Butler, in his foreword, had explained the common view of probably the vast majority of the Fathers of the Council, at which he was a particularly acute observer and participant. Then in 1966, Butler set out his understanding of the whole Conciliar event in his brilliant and rapidly completed book The Theology of Vatican II. This received seriously favourable critical acclaim. Abbot Christopher Butler had emerged from the Council as an international figure.

A.W.