Fortieth Anniversary of Vatican II Symposium (2002)

Vatican II and The Bible

By Robert Murray SJ

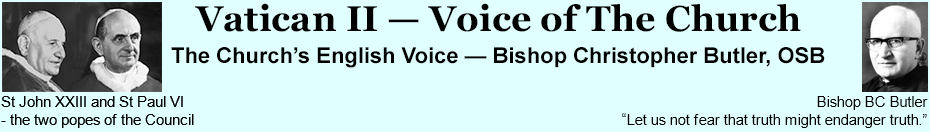

The bible is so fundamental and central to the Second Vatican Council that it is impossible to do justice to this sweeping title in a short paper. The most important teachings of Vatican II are founded on the Bible, more directly than those of any previous ecumenical council. Of its four documents which bear the special title of 'Constitution', clearly the most fundamental one is Dei Verbum (hereafter DV), 'the Word of God', which expounds the Church's faith in God's revelation to humankind in the Bible, in Christ and in all the Church's living tradition. The Constitutions Lumen Gentium (LG), on the Church, and Sacrosanctum Concilium (SC), on the Liturgy, are clearly built on the foundations laid in DV (though not in the sense that it was completed first). Abbot Butler contributed, by speeches or written submissions on points of detail, to the formulation of all three documents, but especially of DV, for which he was a member of the commission which drafted its successive revisions. This is another reason for focussing on it today when we are honouring his memory. This paper has three sections: (1) Why authoritative teaching on Revelation was needed; (2) A sketch of DV, its history, contents and main emphases; (3) A review of the reception of DV since 1965, and of its challenges which still call for a better response.

Dei Verbum represents the first comprehensive teaching on God's Revelation to humankind made by an Ecumenical Council in the Church's history. When Christianity arose in the faith community of Judaism, the reality of communication between God and humans was not in question; what was crucial was the role and nature of Jesus. As the Gospel spread, it met an already existing readiness to believe in divine revelation. Christians recognized 'seeds of the Word' at work, spread by the Holy Spirit in advance of the Gospel.[i] When conflicts arose, they were about interpretation.

The first threat to belief in the unity and continuity of revelation was Marcion's denial that the scriptures and the God they described had any connection with Jesus and the God he revealed.[ii] The Catholic reply was summed up in what is perhaps the first dogmatic formula: Deus est auctor utriusque testamenti, meaning that one and the same God is the initiator of both Covenants and therefore the source and inspirer of the writings held sacred by both Jews and Christians.[iii] Continuing rivalry to the Catholic understanding of revelation came from various movements commonly termed 'Gnostic':[iv] typically these claimed secret traditions from Jesus, incorporated into new systems concerning good and evil spiritual beings, the material world and human nature, in forms incompatible with either Judaism or Christianity.

In the sixteenth century the reality of revelation was not at issue between Catholics and reformers. The Council of Trent's only relevant text briefly states that the truth of the Gospel is contained both in the Bible and in 'traditions' not in scripture but handed down from Christ and the apostles;[v] then follows a reaffirmation of the fuller Catholic canon of scripture. But in the next two centuries the philosophical framework which had supported belief in revelation steadily lost its hold. By the nineteenth century belief in the possibility of revelation needed a new intellectual underpinning and defence against growing unbelief. Vatican I (1869-70), in its short chapter on revelation, concentrated on defending the power of human reason to know God, but more was needed to help people to understand biblical language and interpret it so as to feed living faith.[vi]

In the late nineteenth century a new approach to the historical development of religious thought caused a strong reaction by those whose idea of truth was static. A charge-sheet of heresy was constructed under the name of 'Modernism', and all items on it were condemned by Pius X in 1907. For several decades Catholic biblical scholars suffered an inquisition which imposed almost fundamentalist principles, expressed in responsa issued by the newly-founded Pontifical Biblical Commission. Any use of literary-critical methods, or attempts to trace the intentions of biblical writers in their historical contexts, were discouraged, and were attacked in scurrilous tracts (especially in Italy) as the devil's work.[vii] Those who maintained the honour of Catholic biblical scholarship in this period were led by Fr M.-J. Lagrange, op, who had founded the École Biblique in Jerusalem in 1890. His fidelity to authentic tradition was proof against all sniping, while his scholarship was universally recognized.

At last the injustice to serious exegetes was recognized, and Pius XII, in his encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu (1943), expressly commended a responsible use of critical methods and encouraged Catholic scholars to seek the truth in freedom.[viii] This encyclical paved the way for DV twenty years later. Some questions remained, especially: How does human authorship of biblical books relate to God's 'inspiration'?; In what sense and how far is the whole Bible 'true'?; In the 'Deposit of faith' preserved in the Church, what is the relationship between Bible and Tradition?; What is the role of the holders of teaching authority in the Church in the field of biblical interpretation? Finally, in the light of a liturgical return to sources which was proving fruitful, and the development of lay Christian action powered by group gospel meditation, Catholic pastors and missionaries in many lands saw the need for a pastorally more effective use of the Bible.

A widespread desire had become clear that the Council should produce a major document on Revelation and the use of the Bible, to affirm its central and fundamental place in Catholic belief, worship and teaching, to settle some outstanding questions on principles of interpretation and to encourage a biblical revival.[ix] A drafting commission was appointed, but it was dominated by Italians brought up to view theological truth as enshrined in immutable propositions, and the pastoral duty of bishops as defence of their flocks against error, especially any whiff of Modernism. Central to their first draft was an interpretation of Trent as teaching that divine revelation comes to the Church from two quite separate sources, the Bible and Tradition, under the firm control of episcopal magisterium. The rest of the draft was limited to long-discussed scholastic questions; pastoral motives and new methods did not come in. Together with this text the commission slipped in another, 'On Guarding the Deposit of Faith in its Purity' which aimed to raise to the level of dogmatic anathemas some criticisms of theological trends expressed in the encyclical Humani generis of Pius XII (1950), and to define as dogma a 'penal substitution' theory of the Atonement, a mystery on which Catholic tradition has always declined to canonize one theory. The Council Fathers found the draft on Revelation totally inadequate in the light of Pope John XXIII's expressed vision for the Council and their own sense of pastoral needs, and they criticized the text so radically that the commissioners quietly withdrew both it and the second document, unread. (It can be read in the Council Acta.) A vote on what to do next revealed so many (though less than a two-thirds majority) desiring a completely different spirit and approach that the Pope proposed a new joint commission, combining some of the former members together with scholars trained in critical biblical study and convinced of its value, headed by Cardinal Bea and including, most worthily, Abbot Butler. The joint composition safeguarded fairness but also made a long haul inevitable; this was the main campaign in which the fundamental issue of the Council's essential task and achievement would be fought out, and its toughest battle would be over the 'two sources' theory of scripture and tradition. Three more drafts were presented and discussed in detail before a final text was accepted by a large majority. It was in this process that Dom Christopher made his greatest contribution to the Council's work, though it is a laborious task to trace it in the Acta.[x]

A Summary of the Contents of DV, Drawing Attention to Significant Features

Ch. 1. 'Revelation in itself'. At a late stage the Council chose to open the text with the Biblical and proclamatory phrase 'the Word of God' (which would become the name of the Constitution), rather than the technical theological term 'revelation', though this remains in the subtitle.[xi] God's initiative in communicating with humankind is presented in personal terms rather than dogmatic propositions.[xii] Only at the end of the chapter are two key texts of Vatican I briefly cited. Biblical 'Salvation History' is expressed in terms of God's 'deeds and words intrinsically bound together' so that his works show forth the significance of his words, and vice versa. This process has its climax, centre and full revelation in the person and work of Christ. A scholastic tag, that revelation ended with the death of the last apostle, was rejected in favour of a modest statement that 'no new public revelation is to be expected' till Christ returns. The acceptance of Christ's revelation is what St Paul calls the 'obedience of faith', a free act of each believer in response to the Holy Spirit. This vital little paragraph (1.5) marks the bridge between Christ and the entire body of the faithful in every age.[xiii]

In Ch. 2, 'The Transmission of divine Revelation', the process signalled in 1.5 is spelt out. Christ delivered the gift of revelation to his Apostles and Evangelists, and they to the Church, which, guided by the bishops as successors of the Apostles, is the 'Tradent' of revelation and the tradition of faith.[xiv] The crucial long paragraph 2.8 introduces the Council's solution to the dispute over Revelation and Tradition. Tradition means both the process of handing-on and also the sum of what is handed on.[xv] It develops by growth in understanding through contemplation and study by all believers, among whom the bishops have a special charism for teaching. There is no disjunction between Scripture and Tradition; 'they both flow from the same source, merge together and make for the same end'. The phrase on their mutual relationship almost echoes the phrase in ch.1 about God's Words and Deeds. The last section of ch.2 is a carefully balanced statement on the Church's teaching office, magisterium, in its responsibility to the word of God.[xvi] This chapter is fundamental for the Constitution on the Church (especially ch.2, 'The People of God') and for that on the Liturgy as well as for much in other documents.

Ch.3, 'The Inspiration and Interpretation of Scripture', quietly lays to rest long-standing controversies over 'inspiration', or the relationship of the human authors of biblical books to God's initiative, and over the 'inerrancy' of Scripture, or the question of how God's truth can credibly be ascribed to the Bible.[xvii] God's purpose in revelation is clearly his plan for salvation, not to solve scientific problems, nor need every detail in every narrative, regardless of its nature, be held to be guaranteed by God's veracity. The Bible contains many different literary genres, of which each has its own mode of truth. The key to interpretation is in identifying, as far as possible, the intention of each biblical writer in relation to his historical and cultural circumstances and the genre in which he was writing. Attention to these factors had been branded as heresy in Italy for half a century, till the encyclical of 1943 formally recommended it. Now Catholics can see that it is disregard of these factors which constitutes the error of fundamentalism. But—the Constitution insists—the Bible demands to be read 'in the same Spirit through whom it was written', and within the tradition of faith. The chapter ends by adopting the patristic parallel, beautifully used by St John Chrysostom, between the humility of the Incarnation of the divine Word in human nature, and the 'condescension' of God's Revelation into human language.[xviii]

Ch. 4, 'The Old Testament', is the first part of DV which was not occasioned by any current controversy, and it has an almost patristic ring, approving the Christian tradition of reading the Old Testament symbolically, and repeating the venerable formula 'God the inspirer and originator of both testaments' (auctor does not mean literary author). The continuing value of the Old Testament in itself is very gently asserted; it could have been in place to confess and deplore that Catholics can still speak of it in tones not far from echoes of Marcion. As for Judaism, care is taken not to offend, but the chapter would almost certainly be written differently today, thanks to the increasingly fruitful collaboration of Christian and Jewish scholars, inspired by the Council's document Nostra Aetate.[xix]

With ch. 5, 'The New Testament', we are back with disputed matters, and it was here that Abbot Butler, being on his professional ground, made perhaps his strongest contributions, well explained further in his History of Vatican II. The first section insists on a high Christology as giving the true sense of the New Testament. Next the essential historical value of the Gospels is firmly asserted, but thirdly, it is accepted that after the ascension of Jesus and the gift of the Holy Spirit, there was a period of preaching and transmission, up to the times of the publication of the Gospels, which may have made the gospel tradition also reflect some concerns of the infant churches. On all this, a reasonable use of the techniques of form criticism is commended, as in the encyclical of 1943.[xx] But for the rest, in contrast with these clearly enunciated positions, the rest of the New Testament hardly gets more than a nod.

Ch. 6, 'Holy Scripture in the Life of the Church', is the longest chapter and is of a practical and directive character, calling for a biblical revival in the formation of priests, in the liturgy, in the Church's mission and in almost every aspect of its life. But the chapter is also structured by a powerful theological image. The opening sentence pictures the Church, 'never ceasing—especially in the sacred liturgy—to receive the bread of life from the one table of God's word and Christ's body', and the same eucharistic comparison closes the chapter. This imagery is rooted in St John's Gospel, chapter 6; it was developed by St Augustine and finds a place in The Imitation of Christ. The idea that God's word, as it is met through reading the Bible, works as a kind of sacrament, was dear to Newman, though he never developed it beyond a few pregnant phrases, yet perhaps enough to release its force.[xxi] Newman is never referred to in any document of Vatican II, yet many commentators have discerned his presence behind its teachings.[xxii] This is especially true of DV, from its first emphasis on revelation in personal rather than propositional terms, and the explanation of inspiration and inerrancy, to this last powerful image. It is strange that the conservative opposition steadily at work throughout the debates on DV expressed the fear that the comparison would undermine faith in the real presence of Christ in the eucharist. The Constitution on the Liturgy sets the statement 'He is present in his word, since it is he himself who speaks when the holy Scriptures are read in the Church', parallel to Christ's presence in the sacrifice of the Mass and in the eucharistic elements, in the sacraments, and finally, in the Church gathered for worship.[xxiii] The same document, of course, also spells out more fully the guidelines sketched in DV 6 for a renewed liturgy in the Church. As a whole, this chapter is a powerful conclusion to Dei Verbum, but the best comment on it is to review how it has been received.

A review of the reception of Dei Verbum

Several such reviews have been published over the years since 1965,[xxiv] and on this occasion there is no time for more than a few headings. Just as all the work of Vatican II, regarding so many aspects of the Church's faith and life, called for the establishment of commissions to organize the necessary developments, so has it been for the use of the Bible in the Church. In general the tasks were entrusted to the bishops in their conferences all over the Catholic world, but one central organ was already in place, the Pontifical Biblical Commission.

Since its foundation early in the twentieth century, this has consisted of qualified Catholic bible scholars, but they were at first obliged to issue repressive directives. Since Vatican II its character has entirely changed, so that its periodical publications have been helpful surveys of areas of biblical study and teaching, commended but not imposed by papal authority. The subjects have been 'The Historical Truth of the Gospels' (1964), 'Scripture and Christology' (1985), 'The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church' (1993) and 'The Jewish People and their Sacred Scriptures in the Christian Bible' (2001).

As called for by the Council, there has been a vast enrichment of the lectionary for Mass and the readings for daily prayer of the Church, but all too frequently the Sunday Old Testament reading, carefully chosen to illustrate the Gospel, is omitted, for reasons sometimes understandable, but always regrettable. Here let me emphasize a related matter which is of very practical importance, yet is still too often allowed to go by default. The efficacy of the word of God in the liturgy depends on really good reading, carefully prepared and performed with conviction and care for audibility, right to the back of the church; this requires training. The office of Reader was once a 'Minor Order'; it calls for no less devotion than that of eucharistic ministers. Reading which does not get across is a failed link between God's word and his present people. In contrast, effective reading may help them to go home mentally, as well as sacramentally, nourished even after (God forbid!) an empty sermon.

Preaching which really brings a biblical message home is increasing but, sadly, is not yet universal. To offset my previous allusions to deplorable past activities of some Italian clergy, these have been infinitely outweighed by the wonderful bible readings by Cardinal Martini in Milan Cathedral, with their wider outreach.[xxv] But the renewal of a real biblical culture in the Church has been badly weakened by the departure from active ministry of so many priests young enough to have enjoyed a richer biblical formation, and to have had some preparation for the Council's huge programme of renewal, who thereafter were prohibited from teaching as a ministry in the Church.[xxvi]

However, there is fairly widespread Catholic participation in bible study groups, often fostered by 'Ecclesial movements' such as the Neo-catechumenate;[xxvii] the monastic tradition of Lectio divina is developing in lay forms, often ecumenical; and in some places there is joint study with Jews,[xxviii] which Christians almost always find both enlightening and enriching. A radical desideratum in DV 6 (no. 22) was for the Catholic Church to make peace with the Protestant Bible Societies and work with them. Despite longstanding hostility, full collaboration between the Catholic Biblical Federation and the United Bible Societies was soon established, bringing a notable increase in production of vernacular versions all over the world. Similar collaboration has developed with publishers of daily bible reading aids such as the Bible Reading Fellowship, though in this country, at least, nothing seems to check a lamentable decline in general knowledge of the Bible.

On the whole, the most powerful response to the programmes urged in DV 6 has been outside Europe, in all continents but above all in Latin America. Bible study has been a central activity of the 'base communities' which sprang up especially among the poor; it was their reading of the Bible in the light of their own situation which was the main cradle of liberation theology.[xxix] This movement as developed in Brazil is vividly described by Carlos Mesters in his book Defenseless Flower: A New Reading of the Bible.[xxx]

In conclusion, as a teacher at tertiary level, I must call attention to the potential or actual dangers for Catholic teaching of the Bible as the book of the Church, from the side of some contemporary movements in hermeneutics. Good biblical commentaries and periodicals serving Bible study have multiplied, but too much of both is too full of opaque jargon; more good 'middlebrow' material is needed. I see an urgent need for Catholics in tertiary education to develop a strong middle path, of the highest possible scholarly integrity, between critical study of biblical texts as this is widely practised, and the sterile defensiveness of fundamentalism. Though the brief chapters of Dei Verbum on the Old and New Testaments may now look dated in some respects, this historic document is still a guiding light on our path, and for that we thank God for Christopher Butler, with the other scholarly Council Fathers led by Augustin Bea, and the periti, perhaps especially Yves Congar. And I cannot end without recording my gratitude to Father Christopher for his friendship towards myself.

Back to List of Symposium Speakers

Footnotes

[i] This theme is called the 'Preparation for the Gospel', after a work of this title by Eusebius. Cf. Gaudium et Spes, 22.5, 26 and 57-8. It is also dear to Pope John Paul II: see e.g. his encyclical Dominum et Vivificantem (1986), pp.53-4. Sadly, the Catechism of the Catholic Church omits it at almost every point where it would be appropriate.

[ii] For a sketch see H. Chadwick, The Early Church (Penguin Books, 1967), pp.38-40.

[iii] 'Auctor' used of God should never be translated 'author' in its literary sense, or be taken to imply literal dictation (as Muslims believe the angel Gabriel dictated the Qur'an to Muhammad). Newman held that the primary reference is to the two Covenants: see his On the Inspiration of Holy Scripture (1884), ed. J.D. Holmes and R. Murray (London: Chapman, 1967), pp. 129-31, and Introduction, pp. 55-62.[iv] These had a wide range. See Chadwick (n.2), pp.33-8. Some tendencies towards gnosticism have repeatedly appeared within Christianity (often in the Platonist tradition), while variants flourish perennially beyond the fringes (e.g. Scientology, some New Age movements, etc.).

[v] M. Bévenot, 'Traditiones in the Council of Trent' in Heythrop Journal 4 [1963], pp. 333-43, makes it clear that the term was used to refer to Catholic observances as a whole, under attack by the reformers, not the theological concept of Tradition (capital T) as it would be discussed at Vatican II.[vi] See the neat summary by Avery Dulles, SJ (now Cardinal), Revelation Theology (Burns Oates/ Herder & Herder, 1970), pp. 75-7.

[vii] See J. Levie, SJ, The Bible, Word of God in Words of Men (1958: ET London, Chapman, 1961), chs. 3-4, pp. 40-76, and 122-32.

[viii] Levie, ch.7, pp.133-80; pp.181-90 then carry the history through to 1955. Divino Afflante was published in English by the Catholic Truth Society. The changed attitude to scholars must have given great encouragement to Christopher Butler (see n.20 below).

[ix] On the history see H. Vorgrimler (ed.), Commentary on the Documents of Vatican II (ET London: Burns & Oates, 1969), vol. III, and the racier (but well substantiated) account by 'Xavier Rynne', TheThird Session (London: Faber & Faber, 1965); his whole history is now republished in one volume, Vatican Council II (New York: Orbis, 1999).

[x] Though delivered speeches and written submissions appear under their authors' names, the proposers of all the amendments are designated only by numbers and have to be identified by means of a list in the last volume. This makes one all the more grateful for the help given by Christopher Thomas, 'The Conciliar Contribution of Abbot Christopher Butler', in The Venerabile (Journal of the English College, Rome), vol. 32.2 (2001), 93-101.

[xi] French idiom made it possible to reproduce this order in the version by the Taizé Observers Roger Schutz and Max Thurian in their perceptive commentary, La parole vivante au concile (Taizé: 1966; ET Revelation: A Protestant View, WestminÂster, MD: Newman, 1968). In English it can only be done by recasting the sentence; see the version in N. Tanner (ed.), Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils (London: Sheed & Ward, 1991), vol. II, p. 971.

[xii] This was greeted joyfully by Schutz and Thurian, and is emphasized by Butler in The Theology of Vatican II (London: DLT, 1967; ed.2, 1981), pp. 26-8. His chapter 'Revelation and Inspiration', though only of 27 pages, is an outstanding exposition of the Constitution.

[xiii] Schutz and Thurian praise this paragraph highly (French ed., pp. 77-80). It is sad that the new Catechism, which verbally cites a large proportion of DV, omits 1.5 and replaces it with a strong warning against private revelations. (Whenever personal response to the Holy Spirit comes up, the authors tend to stress human moral fallibility and need for guidance by church authority; cf. Cat. nos. 1783, 1790 on conscience).

[xiv] The whole chapter is redolent of the work of Yves Congar, OP, who was still writing his massive Tradition and Traditions (1960-63; ET London: Burns & Oates, 1966), while serving the Council as one of the leading periti.

[xv] This sentence is not verbatim from DV but is implicit in the thought. Similarly 'Revelation' has an extended range, covering the original experience of the 'word of God', its record in scripture, and the renewed actualization of it whenever it 'gets through' to hearers or readers. Gerald O'Collins, SJ has proposed the useful terms 'foundational' and 'dependent' revelation for the original and the final experiences (Fundamental Theology [London: DLT, 1981], pp. 99-102)

[xvi] It is important for ecclesiology that magisterium till about the mid-nineteenth century referred to the activity of authorized teaching in the Church. The use with a capital 'M', to denote episcopal and especially papal authority, was developed mainly in the anti-Modernist documents. See references (especially to Congar) in the section referring to DV (by R. Murray) in M.J. Walsh (ed.) Commentary on the Catechism of the Catholic Church (London: Chapman, 1994), pp.15-16 with notes 27-34, and Excursus, pp.34-5.

[xvii] Besides Levie (n. 7 above), the 1967 edition of Newman On Inspiration (n.3 above) and commentaries on DV already referred to, B. Vawter's Biblical Inspiration (Philadelphia: Westminster - London: Hutchinson, 1972) is good.

[xviii] See Murray in Walsh, Commentary (n. 16 above), p. 20 and n. 43.

[xix] The Holy See's guidelines for dialogue and teaching in three documents (1965, 1974 and 1985) are available in Catholic-Jewish Relations (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1999).

[xx] Butler spoke strongly for the freedom of Catholic exegetes in the session of 6 October 1964.

[xxi] See Newman On Inspiration (n.3 above), p.114. In 1863 Newman had discussed this concept somewhat more fully in his personal notes (not a finished ms) edited by J. Seynaeve, Cardinal Newman's Doctrine on Holy Scripture (Louvain-Oxford, 1953), pp.127-8.

[xxii] Butler (n.12 above), ch. 2, passim; cf. Murray in Newman, On Inspiration, pp. 92-6.[xxiii] SC, 1, 7.

[xxiv] See (e.g.) E. Bianchi, 'The centrality of the Word of God' in G. Alberigo et al. (eds.), The Reception of Vatican II (ET London: Burns & Oates, 1987), pp. 115-36, and R. Murray, 'Dei Verbum' in A. Hastings (ed.), Modern Catholicism (London: SPCK, 1990), esp. pp. 79-80.

[xxv] J. Wijngaards gave a vivid account in his short article 'Access to God's word', The Tablet, 23 April 1994, pp. 488-9. Martini's professional field had centred on Biblical textual criticism, hardly a subject calculated to fill a huge cathedral and necessitate radio links to other churches. The fruit of his teaching has run to numerous books, translated into many languages.

[xxvi] Murray (n. 24 above), p. 79.

[xxvii] See Bianchi (n. 24 above), pp. 130-32.

[xxviii] For example, the Jewish-Christian Bible Weeks which have been held annually for over thirty years in Bendorf on the Rhine.

[xxix] Well documented and evaluated by Bianchi, pp. 132-6.

[xxx] The article by J. Wijngaards (n. 25 above) includes impressions of his meeting with Carlos Mesters.

Father Robert Murray

Father Robert Murray